In recent years, Albania has made considerable efforts to address corruption, starting in 2016 when Parliament adopted the law on whistleblowing and protection of whistleblowers, following the recommendation of the European Union. While the law itself represents a positive step towards the fight against corruption, there is still a lack of trust in the system, which has resulted in a relatively low number of reported cases.

Concerns have been raised by experts about the response and protection provided to whistleblowers. They suggest that more needs to be done to ensure their safety and prevent potential retaliation. Gentian Progni, an IT expert in Albania, has been criticized for his whistleblowing against corruption cases within the government. Progni expressed disappointment with the lack of support and protection from institutions when the threats against him reached his family members.

Institutions and NGO efforts to increase capacity and awareness

The High Inspectorate for the Declaration and Control of Assets and Conflict of Interests (HIDAACI), the institution responsible for monitoring the implementation of the law in Albania, says that has been engaged in increasing the capacities of the responsible units near public and private authorities charged with the implementation of the law.

In response to the request for information sent on December 4, 2023, this institution informed us that, as part of the “Implementation of legislation for whistle-blowing and protection of whistle-blowers” project, they have carried out an awareness-raising campaign that includes TV spots and online distribution of posters and videos. They have also provided guidelines for whistleblowers in Albania to public authorities, providing necessary information and tools for reporting suspected corruption cases.

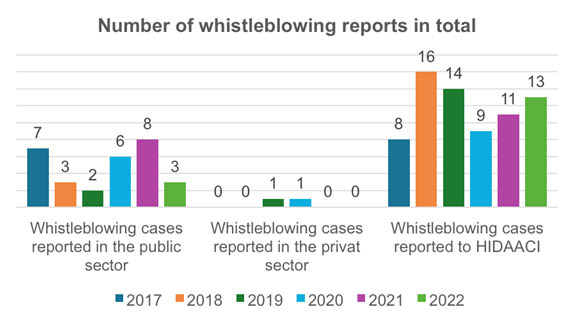

While the initiative taken by HIDAACI in 2017 to share this publication is certainly important, unfortunately, it appears to be the last one. Despite their efforts, the number of reported cases remains relatively low, as the data shows.

In response to reported cases, HIDAACI has conducted administrative investigations where measures taken at the end include fines (which range from $1,000 to $5,000) for the public officials, dismissal of the employees, and resolution of the cases with a conflict of interest. From 2017 to 2022 (the last year of public reporting by this institution), six fines were applied, and five cases resolved.

To get a new perspective, we contacted the Albanian Helsinki Committee, one of the most well-known NGOs in Albania, which has been monitoring HIDAACI’s activities since 2016 to ensure compliance with the whistleblower law. The committee acknowledges the law’s dysfunction but argues that its effectiveness in preventing and detecting corruption comes from a lack of awareness and understanding of it.

“The number of reported cases has remained constant over the years, indicating a lack of trust in the system and fears of retaliation. Additionally, the presence of other reporting platforms can cause confusion and hinder direct reporting to the responsible units, or HIDAACI,” the committee said.

For them, there have been successful cases where the whistleblower law has played a significant role, which involves HIDAACI recommending further investigation for the institutions suspected of corruption and forwarding the cases to relevant investigative institutions. In its 2021 annual report, we found that this institution informed the responsible authorities about reported cases, including the State Audit Office and the state police structures. These cases demonstrate the positive impact of the whistleblower law according to Albanian Helsinki Committee.

For Roden Hoxha, executive director and portfolio manager at the Albanian Center for Quality Journalism (ACQJ), the reports published by HIDAACI do not provide any positive premises for the implementation of this law. The number of reported cases is very low and doesn’t highlight any significant problems that could lead to effective change. The decisions taken by HIDAACI have been in the form of administrative decisions, which have not had any impact.

Some whistleblowers, as Hoxha states, have experienced workplace or employer retaliation, leading to the inference that deficient protection and implementation issues stem from the law’s incomplete nature. “The law’s structure, including internal mini-institutions for whistleblower reporting, narrow scope, and HIDAACI’s role in enforcing it, raises concerns about its independence and executive power,” according to Hoxha.

The whistleblower law faces challenges such as lack of information about rights and protection, fear of retaliation, and the presence of other reporting platforms that may divert individuals from using the designated reporting tool provided by responsible units.

Mirsada Hallunaj, an Albanian political science specialist and Research Associate at the Center for the Study of Democracy and Governance, explains that the law has been poorly implemented in recent years, facing a number of challenges. For her, there are some serious financial violations and abuses that are systematically reported, but the number of employees in public institutions who have reported cases of corruption has decreased.

“The Law on Whistleblowing is complex and requires expertise and sufficient human, administrative, and financial resources, which is also evidenced in the Resolutions of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania for the institution of HIDAACI,” adds Hallunaj.

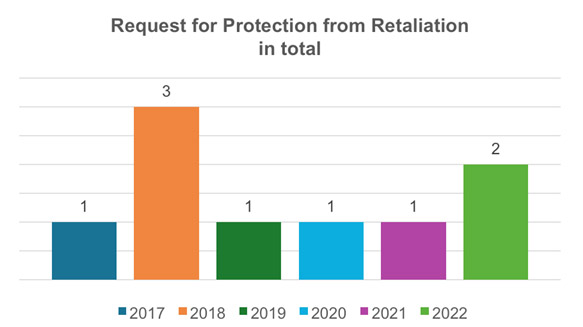

Hallunaj said that despite international conventions providing protection for whistleblowers, the number of requests for protection remains low. She provided us with the complete data, which is also confirmed by what HIDAAC sent us through their RFI response.

Regarding the requests for protection from retaliation from 2017-22, HIDAACI has conducted administrative investigations in only two cases, while for the others it has concluded that there were no acts of retaliation taken against the whistleblowers.

Gentian Progni an Albanian information technology specialist, and technology whistleblower it is not among the two cases. With a reputation for his expertise in IT, Progni has also made a name for himself by shedding light on law violations within Albania’s technology sector. In different public interviews, he has shared his critical insights on corruption cases affecting both public and private institutions. At the same time, he offered solutions to prevent and address these problems, particularly regarding the cyberattacks that have lately targeted Albania.

Speaking about the effectiveness of whistleblower protection laws, Gentian Progni points out that he is not actually protected by this legislation. “Unfortunately, I have been threatened four times with my life in different ways, and one of them was when GPS was installed in my wife’s car. I didn’t receive protection in any of these cases, even though all were published in the media. I didn’t have even a verbal request for protection for me or my family.”

Progni, who has been involved in whistleblowing for three years, says that has received help only three times, and that from civil society. The lack of trust makes him doubt that, even in that case, the help was not that genuine. When he talks about the Albanian media, he says that there is terrible censorship, which makes his role more difficult. “In my opinion, the media is still led by a generation that finds it easier to participate in corruption than to fight it,” said Progni

There are other reports from whistleblowers, such as Progni, who have stated that in some cases the media revealed their identities, endangering not only their jobs but also their lives. Regarding his cases Progni announced that for this year, the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Corruption and Organized Crime has started investigations into one of them, adding that this will serve as a test for the institution’s desire for progress.

Media’s Role in Shaping Perceptions of Whistleblower Law

The Albanian media has played a significant role in shaping public perception towards the law and whistleblowers, initially portraying it as the “Spies Law,” which carries a negative connotation associated with Albania’s communist past. This negative perception has proven difficult to change and has affected overall views on the law and its practices.

“Our communist past is still present,” says sociologist Entela Binjaku, highlighting how traces of the regime are everywhere. Consequently, initiatives by the whistleblower service are often perceived as espionage-like activities within our social psyche.

Using the term “spy” to promote the “Whistleblowing Law,” the Albanian media, has instead brought back a reminiscence of the past, causing significant suffering for families and individuals.

“The use of this term brings back to the collective memory bitter emotions and experiences of the fear of “spying”, causing society to recollect the infamous communist proclamation that ‘of three persons, one of them is a spy’, explains Binjaku. These people play a crucial role in our society, yet they often face societal prejudices, ridicule, and underestimation of their job. She emphasizes the need for professional and empowering support systems under the Law on Whistleblower Protection to address the challenges faced by whistleblowers, who often play multiple roles such as parents, friends, etc.

The implementation of the whistleblower law in Albania has seen both challenges and progress. While the adoption of the law itself is a positive step in the fight against corruption, there are many obstacles to overcome. Trust in the system remains low, leading to a relatively low number of reported cases. Concerns about the protection provided to whistleblowers highlight the need for more measures to ensure their safety and prevent retaliation. To improve the implementation of the law, it is crucial for both the media and civil society to increase public awareness, while the responsible institutions must actively promote whistleblowing practices.