By Arlis Alikaj

Pëllumb Gjini is the former mayor of the village of Steblevë in the north part of Shebenik-Jabllanica, the largest national park in Albania, an area recognized and protected by UNESCO and Albanian law. He helped organize local elders and stakeholders for the creation of the national park in 2008 after loggers caused huge damage for years.

“But, ironically, the situation did not improve and the environmental massacre continues”, says Pëllumb.

Pëllumb Gjini found himself at the head of this movement unintentionally. Steblevë is part of the broader Librazhd region, and the mayor of Librazhd has authority over the village mayors in the region. Gjini was fired from his position for his activism by the mayor of Librazhd, who represented the Socialist Party. After being fired from the Socialist Party, a party he once believed would bring change, Pëllumb saw his beloved country being destroyed by illegal logging. The political power in Tirana seemed to ignore the destruction happening outside their windows, but Pëllumb could no longer remain silent.

“I received a complaint letter and, later on, a warning letter for not focusing on my job, but rather on problems. After getting these letters from the mayor of Librazhd and other elected regional institutions, like the Regional Environment Office of Forestry and Tourism, I started writing fewer reports and included more positive language in my submissions. However, I also spoke to local media and raised awareness through environmental forums, which ultimately got me into ‘trouble’ and led to me being fired,” said Pëllumb.

His statements, supported by documents and data he had collected over the years, caused a stir in the media. But, with this action, he had also taken on a heavy burden. His family faced threats and he found himself under constant psychological pressure. “I could not do this as long as I was in the role of the [party] functionary, the mayor. Only after I was fired, I no longer felt suffocated and could tell what was happening”, concludes Pëllumb.

In a country where transparency is often defeated by political maneuvering, the voices of whistleblowers serve as a testament to courage and truth. The whistleblowers’ journey is often perilous, but in the end they dared to speak out against corruption within Albania’s political landscape, highlighting the systematic efforts to suppress dissent and the resilience required to challenge it.

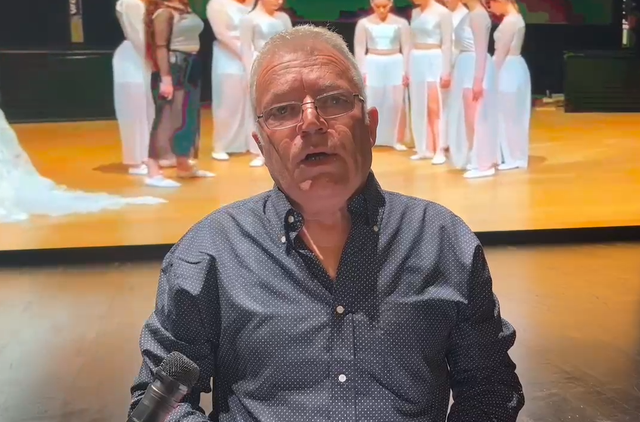

In this picture, Pëllumb Gjini, a former municipal leader and environmental advocate, stands as a prominent whistleblower fighting against illegal logging in Albania’s largest national park, symbolizing the struggle for transparency and public accountability. (Photo credit: Arlis Alikaj)

Klajdi Marku: I told the truth, but it cost me my job

Meanwhile, in Fier, Klajdi Marku, another rebel voice, director of the “Bylis” Theater, was preparing for his battle. When he attended an art event in Athens that the government claimed would have a large turnout, Klajdi saw that the numbers had been manipulated. More than artistically, the event served as propaganda for the government of Prime Minister Edi Rama.

The Prime Minister held the art event in Athens to engage with the large Albanian diaspora residing there. This event aimed to strengthen cultural ties, promote Albanian art, and celebrate the contributions of Albanians living abroad. Today, roughly 500,000 Albanians have permanent residence in Greece, making them by far the biggest immigrant population in the country of 10 million.

Klajdi decided to speak out. By exposing this manipulation, he risked not only his career, but also his personal safety. However, Klajdi knew that to remain silent was to become an accomplice in a great deception, and therefore, he chose to speak.

“The truth is that we were forced to go to Prime Minister Rama’s rally in Athens. We were with our troupe for a show in Corinth, the band asked me to be part of the activity and so we went. It was clear that it was not a voluntary participation.” He explained that the consequence of the publication of this case was his resignation, an imposed action. “I chose to tell the truth, even though I knew it could cost me my job,” added Marku.

In this picture, Klajdi Marku, director of the “Bylis” Theater, advocates for artistic integrity and transparency, challenging government propaganda. (Photo credit: Facebook)

Tactics of silence

An anonymous source within the Socialist Party revealed that these actions were not isolated incidents, but part of a larger tactic to silence dissent. “Anyone who tries to speak out, the source says, is silenced, and may even face trumped-up charges.” It is a psychological game where the party aims to break the spirit of any whistleblower who dares to challenge the system. In short, the government puts pressure in every form so that people don’t speak”, concludes the source.

The well-known lawyer, Roden Hoxha, who once worked for the Albanian State Advocature says that whistleblowers often do not report because they fear of potential retaliation by the employer. The official system for whistleblowing does not protect the whistleblower’s anonymity and privacy, and its usage rate is low.

The High Inspectorate of Declaration and Control of Assets and Conflict of Interest, with the acronym ILDKPI, “is the institution charged by law to monitor the process. The figures published by it in the annual reports are ridiculous, the whole law has been built backwards”, comments Rodeni further.

Ardita Kolmarku, director of the Law Clinic and a civil society project manager, says that the number of whistleblowers is decreasing. Although the law has been established about 8 years ago for the public sector and 7 years ago for the private sector Law 60/ 2016 “On whistleblowing and protection of whistleblowers” this law is not effective. This law, borrowed from global (such as the US) and European best practices, aimed to prevent corruption committed by public officials and those working for private entities. Although enough time has passed to test this legal act and the by-laws issued in its implementation, it is worth saying that the enforceability remains weak due to several factors and conditions mentioned in a number of monitoring reports of the organizations local NGOs, such as the Albanian Helsinki Committee. In national surveys, it has been emphasized that the law is not recognized by employees.