by Ina Allkanjari

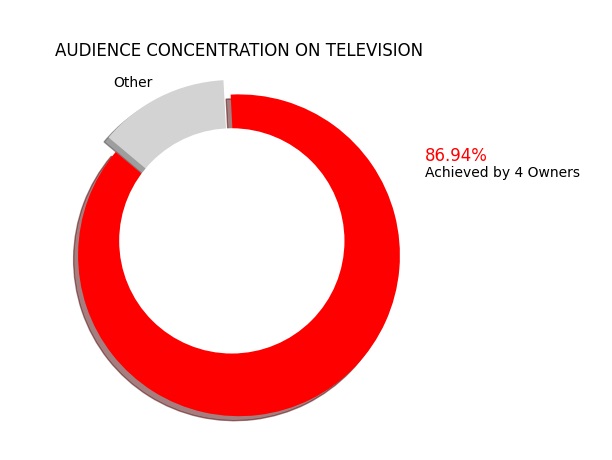

Albania’s media is at a critical point, with growing worries about the concentration of media ownership, political control, and the risks faced by journalists and whistleblowers trying to expose corruption and wrongdoing. The Media Ownership Monitor, a study conducted on 2023 by BIRN (the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network) and the Global Media Registry revealed that just four families control nearly 87% of Albania’s media audience, a stark increase from just 47% in 2018. This consolidation of media power has far-reaching implications, both for the integrity of journalism and for those brave enough to expose corruption and abuse of power.

Despite ongoing talks for EU membership, media freedom in Albania is getting worse, raising serious concerns about the country’s commitment to transparency, democracy, and free speech. The 2024 World Press Freedom Index, from Reporters Without Borders, ranks Albania 99th, just above Turkey, showing a worrying decline in press freedom.

Media Ownership Monitor study, Audience Concentration in Albania

Media ownership: A growing problem for whistleblowers to come forward

The concentration of media ownership in Albania, with a few powerful families controlling most of the media, links business, politics, and media ownership in ways that threaten press freedom and puts whistleblowers at greater risk.

According to Lutfi Dervishi, a well-known media expert, this concentration has greatly weakened independent journalism. “The media is often controlled or influenced by narrow political and economic interests, which limits journalists’ ability to report freely. This creates an environment where hot topics or investigations involving powerful political or economic figures are censored or treated with kid gloves,” Dervishi explains.

Dervishi explains that whistleblowers are subject to a combination of legal and social obstacles, making it difficult for them to come forward.

“Whistleblowers in Albania face a series of major challenges, including the absence of adequate legal protection, social stigma, and fear of retaliation. Furthermore, bureaucratic delays and the lack of an effective system for reporting and tracking cases make many whistleblowers feel insecure about going public,” Dervishi says.

Vladimir Karaj, an investigative journalist with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), adds that the links between business and media in Albania have never been fully transparent, even though the situation is widely known by most professionals. He explains that the business interests of those who have invested in media, using it to maintain beneficial relationships with politics, are mentioned in nearly all reports on this topic as one of the main obstacles to media freedom in the country.

“This unhealthy relationship, where the media serves the economic interests of a small group of investors, obviously has consequences for journalism,” Vladimir Karaj notes.

Karaj reflects on his own experiences and the broader challenges faced by journalists in Albania. “Certainly, in over 22 years of work, I have experienced pressure or threats, this has happened several times. There is no specific plan for how to deal with pressure or threats because these things can’t be predicted,” Karaj says. “The increase in cases of threats and attacks against journalists certainly leads to censorship and discourages journalists from conducting research and investigations, or even reporting on issues that could have consequences for them,” he concludes.

The role of political and business interests

The close relationship between media owners and political elites further complicates the situation for both journalists and whistleblowers. In many cases, media outlets avoid reporting on stories that could expose the interests of the media owners or their political allies. Ben Andoni, a well-known journalist in Albania, describes the pressures journalists face to avoid certain topics. “You cannot report well and openly if you know that your owner has specific interests. Self-censorship is one of the elements that has distorted the Albanian media,” Andoni says.

Ben Andoni further explains how censorship, both from external forces and internal self-censorship, negatively affects whistleblowers’ ability to come forward and the effectiveness of investigative journalism in Albania.

“True whistleblowers face a huge challenge,” says Andoni. “First, when faced with a massive level of corruption, they must be careful and gather as much evidence as possible to protect themselves. Additionally, they must always think about the consequences of coming forward. Given the level of crime in the country, they must also prepare for the worst-case scenario,” Andoni adds.

According to Andoni, the media does not serve as a reliable ally for whistleblowers. He adds that in many cases, whistleblowers are used by the media for sensational stories rather than for uncovering serious problems. “In this environment, whistleblowers risk a lot when they come forward. Therefore, true whistleblowing cases are few and very difficult to prove. The first barrier is the media themselves, which are closely tied to economic interests, often lacking transparency,” he says.

The danger for whistleblowers

While there are laws meant to protect whistleblowers, they are often poorly enforced, and many individuals are afraid to come forward, as they may face significant risks, from losing their job, to legal charges, or even physical harm.

Dorian Matlija, a media expert and lawyer, explains that the concentration of media ownership makes the situation worse for whistleblowers. “As the law stands, whistleblowers are supposed to report through official channels, but often, they don’t trust those channels. In many cases, they end up turning to journalists instead,” Matlija says.

The situation gets more complicated because of the control a few families have over the media. “But with the media being controlled by just a few families with political connections, how can whistleblowers feel safe?” Matlija asks. “The media outlets might not be able or willing to protect their sources if those sources threaten the interests of the owners. So, if they don’t trust the journalist, or if they fear that their story won’t be published because of the media owner has political or business interests at stake, it creates a serious problem, and the corruption cases will never come to light.”

One of the most high-profile suspected cases of whistleblower protection in Albania occurred in 2021, when the news website Lapsi.al published a leaked voter database allegedly used by the ruling Socialist Party during the 2021 elections. The leaked database contained sensitive information about over 900,000 Albanian citizens, including their voting preferences. When Lapsi.al refused to hand over the database to authorities, the journalists involved faced pressure from the government and were threatened with legal action, including a court order demanding the seizure of their materials. This would have exposed the whistleblower’s identity, undermining the protections that journalists are supposed to offer.

“This case showed how the media in Albania is not fully equipped to protect journalist and whistleblowers,” says Matlija, who represented Lapsi.al in the case. “The problem was the lack of guarantees for journalists to protect the confidentiality of their sources and other secrets, as well as the absence of a guarantee that the system should listen to the journalist before any decisions are made,” he says.

This judicial act was challenged at the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled in favor of the journalists. “Even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in favor of the journalists, there is still a lack of adequate legal protection for whistleblowers and journalists who work with them.”

According to Matlija, since 2021 the legal environment in Albania remains hostile to independent journalism and whistleblowers. He states that the situation has worsened, particularly due to the Special Prosecution against Corruption (SPAK)’s aggressive stance on journalist information.

“So far, no court has provided a single guarantee that at least journalists and their communications with whistleblowers will be protected. They can be exposed, and if that happens, it’s over, that’s it. Because the political situation is dominant in Albania, politics controls every sphere, and once you are exposed, you are destroyed as a source of information and as a whistleblower,” says Matlija.

The costs for exposing corruption

Journalists in Albania also face physical threats and harassment. Investigative reporters who challenge powerful political or business figures are often targeted for intimidation, violence, or exclusion from important events. Klevi Muka, a journalist in Albania, recalls an incident in 2022 when he was banned from attending press conferences by the Prime Minister after asking tough questions.

“After I asked a question to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, I was personally excluded by the Prime Minister from attending future press conferences,” Muka says. “Immediately after the conference, I went to the newsroom, where I saw that I was no longer welcomed there either. They joined the Prime Minister’s decision to exclude me from the press conferences and even went further, asking for my dismissal,” Muka explains.

He also highlights the challenges journalists face when working with whistleblowers in Albania.

“Whistleblowers and sources are somewhat skeptical about cooperating with journalists, although fortunately, my colleagues have always done a good job of protecting their identities. Whistleblowers are more hesitant to work with journalists in Albania, at least, compared to the region, we have less cooperation with whistleblowers,” concludes Muka.

Klodiana Lala, a journalist known for her investigations into organized crime and corruption, faced even more severe threats. It was one of the most high-profile cases that occurred in 2018, when Lala became the target of a violent attack. After publishing a series of reports linking politicians to criminal groups, Lala and her family were subjected to an assault, with their home being shot at by unidentified individuals.

“It was one of the most shocking and difficult moments of my entire life. I believe that protective mechanisms should be established so that journalists can work in a safe environment. Fake news against journalists has become a serious concern, and many journalists have remained silent and no longer report on cases of corruption,” says Lala.

In Albania, investigative journalists face a tough challenge, especially when it comes to working with whistleblowers. Klodiana Lala, explains that many whistleblowers are too afraid to speak out because they fear for their safety. This fear makes it hard for journalists to get the information they need to uncover important truths, creating a major obstacle to press freedom and transparency in the country.

“Journalists in Albania have been facing closed doors for years from whistleblowers who are terrified for their lives.”

Digital threads, smear campaigns and lawsuits

In recent years, Albania has also seen an alarming rise in SLAPP lawsuits—Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation. These lawsuits are designed to intimidate journalists, whistleblowers, and activists, discouraging them from speaking out or exposing corruption.

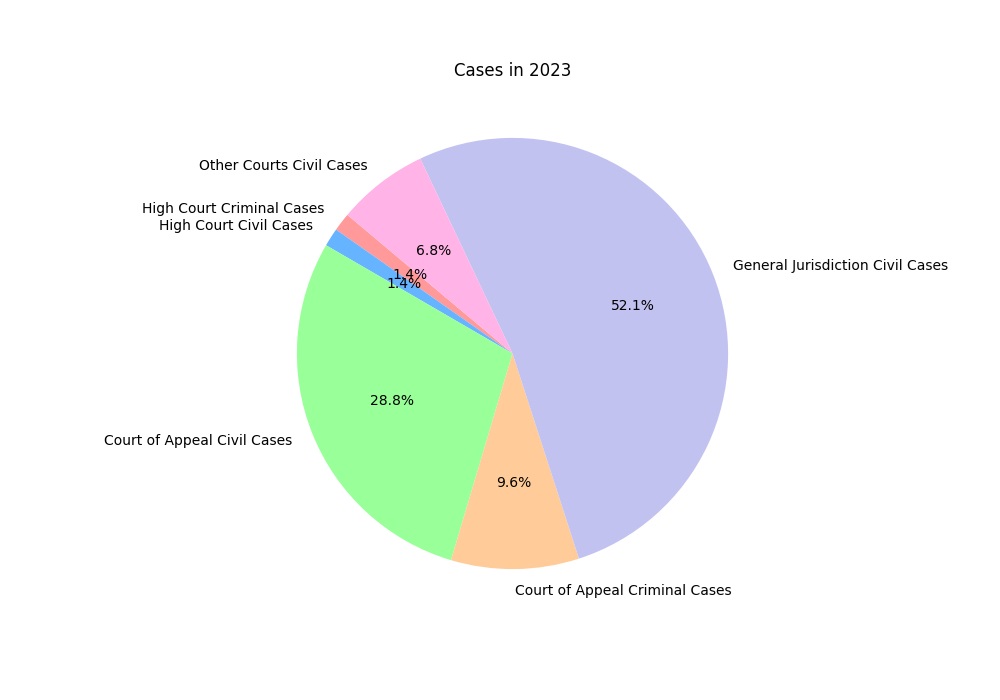

In a 2023 report of SafeJournalists.net, the number of lawsuits against media and journalists in Albania, nearly doubled from 30 cases in 2022 to 73 in 2023. This sharp increase is a worrying sign of how those in power are using the legal system to harass and intimidate journalists. Blerjana Bino, the director of SCiDEV, a media freedom advocacy group, highlights the growing use of SLAPP lawsuits in Albania.

Lawsuits against journalists and media workers in Albania for 2023, data from SafeJournalists report

“These lawsuits place a heavy legal, financial, and psychological burden on journalists and whistleblowers, creating a climate of fear and self-censorship,” Bino says. “The use of SLAPP lawsuits, backed by powerful political or business interests, makes it difficult for journalists to practice their profession independently and report on issues like corruption and abuse of power,” add Bino.

In October 2024, a coordinated smear campaign was launched against SCiDEV, and its director Blerjana Bino, following the release of a report by SCiDEV in collaboration with Osservatorio Balcani i Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT), documenting the alarming rise of legal and work related verbal and physical assaults on reporters.

“These attacks were aimed at discrediting our work in defending media freedom and ensuring the safety of journalists, as well as to discourage our efforts to promote independent and professional journalism in Albania. The goal was not just to tarnish our reputation but to silence us and deter our commitment to promoting independent journalism,” says Bino.

This ongoing pressure is part of a larger problem in Albania, where journalists and whistleblowers face increasing threats and intimidation from politicians, media owners, and powerful individuals. Bino highlights this concerning trend, noting that in 2024, over 30 cases of threats and attacks against journalists were recorded, most of which came from well-known political figures or private individuals, including media owners.

“A concerning phenomenon we have noticed is the hesitation of journalists to report cases of intimidation or pressure, especially when they come from media owners or political figures. This has created a sort of ‘normalization’, where these problematic practices have been accepted as something journalists have simply become accustomed to,” says Bino.

The concentration of media ownership in Albania has led to a dangerous environment where independent journalism is suppressed, whistleblowers are silenced, and the public’s right to information is compromised. Despite the growing number of investigative journalists striving to expose corruption, journalists and whistleblowers face increasing threats of retaliation, harassment, and legal challenges, while media outlets that might otherwise serve as a check on power are too often controlled by business and political elites, making it difficult for individuals to safely come forward.