On the 13th of June, 2023, the Center for the Study of Democracy and Governance in Albania, which also serves as the Secretariat of the Southeast Europe Coalition on Whistleblower Protection, organized a conference on the transposition of the EU Directive. Guest speakers were representatives of the Coalition’s membership network in the EU Member States of Southeast Europe. Based on the Coalition’s work to monitor and evaluate the transposition of the EU Directive on Whistleblowing in Croatia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania, this event had the objective of sharing the findings and lessons drawn from the process in these countries with the countries of the Western Balkans.

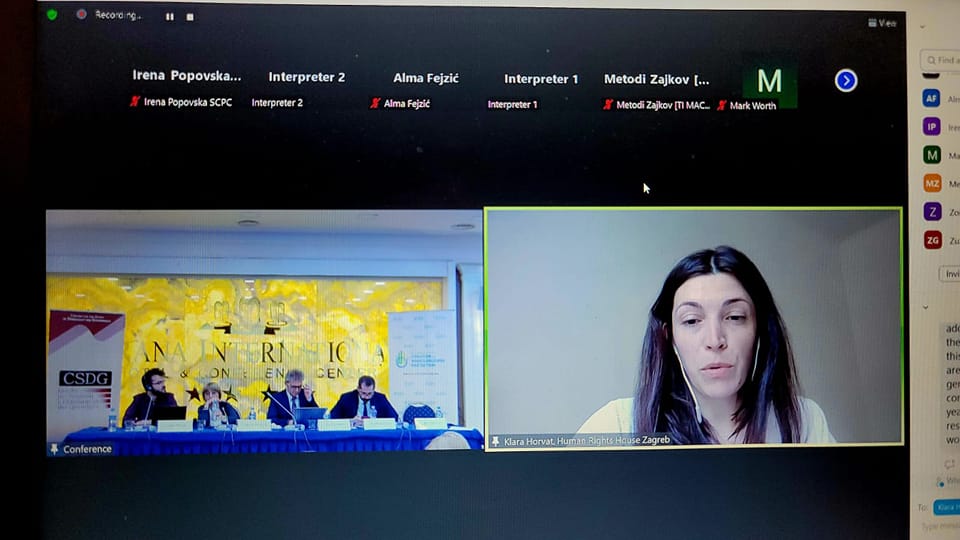

Representative of the EU Delegation in Albania, Peter Danis, attended the conference together with representatives of state institutions, such as the High Inspectorate of Declaration and Audit of Assets and Conflict of Interest, the Ministry of Justice and the Agency for Prevention of Corruption in Kosovo and North Macedonia. The event occurred in a hybrid form, facilitating interaction with representatives of other regional CSOs and members of the Coalition.

The event was opened by welcoming and introductory remarks from Arjan Dyrmishi, Coalition co-coordinator and executive director of the Center for the Study of Democracy and Governance, followed by remarks from the EU Delegation in Albania representative Peter Danis. Peter Danis, a program officer in the area of the Rule of Law and Good Governance, emphasized that the Directive is a result of a long process reflecting on the experiences in the EU. Importantly, it is not just a formality for either Member States nor aspiring countries for EU membership but an essential tool in combating corruption and a vital component of the EU project. Some of the main challenges to be addressed include raising awareness and educating people, institutions, public officials, and the NGO sector on the role and importance of whistleblowers; legal harmonization across legal frameworks of different countries; dealing with organization resistance to the law; promoting a cultural shift and last but not least, providing whistleblower safety and anti-retaliation measures.

Mirela Gega from the High Inspectorate and Rovena Pregja from the Ministry of Justice in Albania provided an overview of their mission and data. The High Inspectorate has broadened its competencies since 2016 to monitor the implementation of whistleblower law but also to serve as a mechanism for whistleblowing. So far, it has issued 208 administrative measures on organizations (both public and private) that have not complied with the law. Out of 30 whistleblower cases, only 2 pertain to the private sector. In addition, Pregja emphasized that the transposition of the Directive is part and priority of the Albanian government’s plan of European integration.

Despite some referrals of some EU Member States to the European Court of Justice for delaying the transposition of the EU Whistleblower Directive, notably, 23 EU Member States have transposed the Directive. Civil society has been active in the working groups and public consultation, especially in the Member States of the region – reports Maria Yordanova from the Center for the Study of Democracy in Bulgaria, Klara Horvat from Human Rights House Zagreb, Angelos Kaskanis from Transparency International Greece and Andrei Mascut from Romanian Academic Society. For instance, the working group in Croatia consisted of state institutions, academia, and CSOs. Notably, the CSOs had a lot of disapproval regarding the law. Upon publication for public consultation, the draft received over 100 comments, of which 28 were entirely or partially accepted.

Greece, however, presents itself as an outlier, in that companies and the private sector showed more interest in adopting the Directive than the public sector. Greece also presents additional challenges since issues of immigration and environmentalism are considered part of national security. Since the EU Directive does not include national security issues, this offers the Member States the possibility to have as many topics of public interest under ‘national security,’ thus discouraging whistleblowers from reporting on corruption in various areas. Moreover, the Directive foresees the protection not only of whistleblowers but also their immediate family members from retaliation. However, as to how this shall be implemented in practice, it is still largely unclear.

To understand the trends in the region regarding whistleblowing and corruption, representatives from state institutions gave us an overview of the most critical data. Jelena Perovic from Montenegro talked about an increase from 2021 in whistleblower cases by 30 percent. Only a third use anonymous reporting channels, a relatively good indicator of trust in compliance officers and the law. Yll Buleshkaj from Kosovo also emphasized an increase in reporting wrongdoings, from 10 cases to 39 and finally 100 in these past three years, respectively. More needs to be done, indeed, but another good indicator is that in terms of gender, 50 percent of whistleblowers this year have been women.

Irena Popovska from North Macedonia talked about recent whistleblowers who have been granted protection and reinstated into their workplaces, a positive sign for the effectiveness of the law. Training and capacity-building programs continue to help deal with whistleblower cases. Finally, Emiljano Kondi from Albania raised some fundamental issues concerning the harmonization of the legislation with the EU Directive but also stresses points of divergence that may be addressed, such as incorporating a sectoral approach, looking into the number of employees of an institution or business to make them subjects of the law, and incorporating sanctions or mechanisms for the protection of whistleblowers already in the early stages of the reporting process.

As a final note of the discussion, Coalition’s outreach specialist spoke about the problems in the work of various member CSOs, especially in raising awareness regarding whistleblowing. One such problem is state authorities’ lack of willingness to participate in public discussions, interviews, and the media. More active involvement and publicity would signal to the public that the authorities take whistleblowing seriously and provide further encouragement for reporting wrongdoings and corruption practices.