“Being a whistleblower in Montenegro is difficult. Nobody enjoys living in uncertainty and worrying about their family’s well-being, but it comes from within and I had to react to obvious irregularities.”

That’s how Milisav Dragojević, a retired engineer and one of Montenegro’s first public whistleblowers, describes his experiences reporting misconduct and safety concerns at the national railway company (ŽPCG).

Dragojević, who worked at the company for more than 40 years, was suspended in 2013 after exposing what he called subpar train maintenance, underqualified staff and other safety violations. After a three-year trial, he won his case against ŽPCG in 2019. A Basic Court judge in Podgorica ruled he was improperly suspended and ordered the company to pay him €3000 in compensation. During the trial, the Agency for the Prevention of Corruption (APC) supported Dragojević by documenting the retaliation and helping him return to work after being suspended.

The Dragojević case shows two things: whistleblowing is a powerful tool in the fight against corruption in Montenegro, but it requires additional institutional support, courage and patience.

Whistleblower Reports Keep Piling Up

Whistleblowing in Montenegro is regulated by the Law on the Prevention of Corruption, making it the only country in the region without a special act on whistleblower protection. The European Commission said last year that “further sustained results are needed” to improve the status of whistleblowers.

The APC agrees that a comprehensive approach to this legal concept is important in order to ensure more effective protection. More specifically, a dedicated law could:

- give power to the APC to order protection rather than recommend it,

- ensure protection if a person makes an honest error in filing a report,

- increase financial penalties for violations, and

- streamline and speed up investigation procedures for the benefit of whistleblowers.

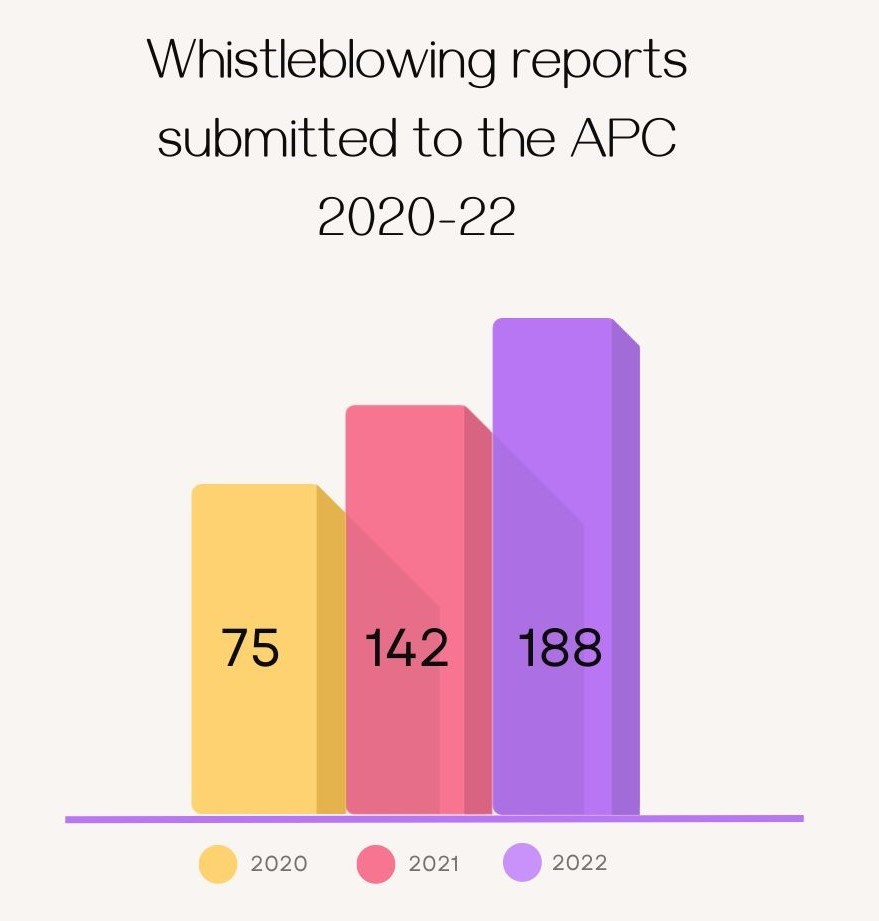

However, an APC spokesperson told the Southeast Europe Coalition on Whistleblower Protection that the current law complies “to a great extent” with the 2019 EU Whistleblowing Directive. The law broadly defines whistleblowing because it allows any person or company to submit a report. According to the APC, that’s one of the main reasons why the number of corruption-related reports keeps increasing year after year.

In the first six months of 2023, the APC received 110 whistleblower reports, marking the highest influx of submissions in a half-year period since its inception in 2016. “It is evident that whistleblowers have the determination and willingness to report various forms of irregularities to our institution”, the spokesperson told the Coalition.

Zorana Marković, executive director of the Centre for Development of Non-Governmental Organizations (CRNVO), also thinks the current law provides a good definition of the term “whistleblower.”

“There is a wide range of actions for which the whistleblower is protected. Everything can be reported to the Agency, including violations of ethical norms. No state goes that far with regard to what a whistleblower can file a report for,” Marković explained.

On the other hand, she believes that the APC’s protection mechanisms are weak and insufficient. “The Agency can give nothing but recommendations to the institutions that break the law, but recommendations aren’t powerful enough. This greatly affects the enthusiasm of individuals and the community as a whole to actually report such misconduct.”

In her opinion, the sheer range of penalties for ignoring the APC’s recommendations is quite broad. “I think the maximum sentence would be very effective.” According to the Law on Prevention of Corruption, fines can range from €1,000 to €20,000 for institutions, and €500 to €2,000 for civil servants.

| The APC’s Report Card on Whistleblower Protection Although it is an incomplete protection mechanism, the APC’s recommendations have been successful in nearly every case. Many whistleblowers have been reinstated to their jobs or protected from being fired because of the agency’s efforts. Since 2016 the agency has received 36 requests for whistleblower protection. It has granted 12 requests – and in all but one case the employer complied and the whistleblower was protected. The agency has denied 17 requests for a range of reasons, while 6 cases are ongoing and 1 was terminated due to insufficient documentation. Two people who asked for physical protection were referred to police for additional assistance. |

Whistleblowers Lack Complete Legal Assistance

Marković notes that the APC provides “expert assistance” to whistleblowers in court cases, such as providing documentation and helping to prove the causal connection between making a report and suffering retaliation.

“That kind of help is not enough. I think Montenegro’s legislative framework needs to be improved in this area,” said Marković.

Her opinion aligns with the findings of the Regional Anti-Corruption Initiative (RAI), an intergovernmental agency based in Sarajevo. A 2021 RAI study found Montenegro’s law “should be modified to provide legal assistance, and attorney fees paid by the defendant in proceedings where the whistleblower obtains relief.”

Expert advice, as RAI suggests, is not a substitute for legal representation. On the contrary, it leaves the whistleblower without assistance against the employer’s reverse burden of proof. “Whistleblowers need counsel for their rights to be realized in practice. The effect is that many whistleblowers will be unable to afford to exercise their rights,” RAI warned.

| When do Whistleblowers Have the Right to Protection? The Law on the Prevention of Corruption says people have a right to protection if they have been harmed or fear retaliation, especially if: their life, health, and property are threatened they lost their job or if their job position has been terminated or changed their job description and conditions have changed disciplinary proceedings were initiated against them they are prohibited from accessing work-related means or information they have been denied professional development and advancement |

The Subtleties of Whistleblower Protection

Every time a whistleblower files a report, the APC decides whether or not to intervene in the case and whether or not this person was retaliated against. This often creates confusion terminology-wise.

Over the past few years, civil society activists, citizens and media outlets have talked frequently about obtaining “whistleblower status,” which is a slight misconception. The APC makes decisions whether to assist whistleblowers and come to their defense, but the agency does not formally assign whistleblower “status” to people.

Any person or company that files a corruption-related report automatically becomes a whistleblower. In other words, there is no need for the APC to officially grant such status to anyone. However, this also emphasizes the need to raise awareness among citizens and the general public.

Marković says this uncertainty reveals practical problems in this field. “Whistleblower status is not granted in Montenegro, but most people think it is. That goes to show how uninformed we really are, which means it’s crucial to better promote whistleblowing,” she explained.

Dragojević also believes it is extremely important that the media have the right approach toward this issue. “Nothing can be done without the media. People need to be encouraged, and the media must promote whistleblowing as the way of coping with corruption,” he said.

The APC, on the other hand, says it is fully committed to awareness raising: “We have carried out educational activities for different target groups and cooperated with the media and the NGO sector. Through continuous campaigns, we have tried to strengthen the knowledge of the general public and to encourage them to report corruption.”

| More Public Information Needed RAI concluded Montenegro should expand its law to appoint an agency responsible for public education and outreach on the importance and benefits of whistleblower rights. “The law should instruct the Agency to prepare annual reports and maintain an education program that, through training and public education, informs citizens about the importance of whistleblowing in preventing and fighting corruption, as well as about whistleblower rights.” The good thing, RAI noted, is that the current law provides “broader protection than a law merely for employees.” In addition, it successfully covers almost all forms of retaliation, as well as the “possibility of retaliation.” |

The Long and Winding Road of Whistleblowing Yields Significant Results

The APC admits the decision to report crime or corruption is quite challenging – not just in Montenegro, but in the whole of Europe. This mainly has to do with the fact that most communities don’t see whistleblowers as useful elements, but rather as a threat to members.

Still, the agency encourages people who witness corruption to file a report to the agency. “If we take into account the number of submitted whistleblower reports and requests for protection, the number of completed cases…it is obvious that Montenegro has established a rich practice in this area,” the spokesperson explained.

Asked if he would be willing to blow the whistle again, Dragojević told the Coalition he “surely would.” He says, “I didn’t make a hasty decision back then. I just couldn’t keep witnessing wrongdoing, so I had to react and speak up.”

Dragojević encouraged potential whistleblowers to follow his lead, but only after thinking it through. “If they want to become whistleblowers, then they have to be persistent. They must use all available means, including the Agency, media, and NGOs. And bear in mind – justice is slow but attainable.”